Photo: Hiwa Talaei – Pexels

What makes something beautiful? Have you ever stopped to ask that question? It’s not as easy as you might at first think. You might be able to identify things / people / concepts that you find beautiful. But that doesn’t help in understanding why you find those things beautiful.

In the last post, we began to consider Beauty – and in particular the thinking of Jonathan Edwards about beauty. We saw that we all long for beauty; we considered (and began to answer) various objections to thinking about beauty; and we began to consider what ultimate beauty consists of.

In the next few posts we will discover the forms of beauty that our beautiful God has provided us with – as one person writes, there is a ‘Cycle of beauty that begins with the Lord, extends to creation, takes personal bodily form in Christ, is displayed corporately by the Church, (and) culminates in heaven’ (Strachan and Sweeney, Jonathan Edwards on Beauty).

But before we do that, we need to pause to ask the question: what makes something beautiful? For that matter, what is beauty? That is the purpose of this post.

What is beauty?

Jonathan Edwards thought a good deal about beauty – and what makes something beautiful. He wrote:

There has been nothing more without a definition than excellency (beauty), although it is what we are more concerned with than anything else.

The Mind

Symmetry, harmony, order, unity

Think of the beauty of a human face, a view captured in a photograph, or a piece of music. What do we find beautiful about them? We could start off by considering their symmetry (the different parts are symmetrical); the harmony between different parts; the order which is displayed; and their unity (everything fitting together into a coherent whole).

For example, the leaf at the top of this post is beautiful. There is a symmetry between the different parts of the leaf. The different parts of the leaf appear and work in harmony with each other. There is an order to the leaf – each part has its own place. And there is a unity – it all fits and works together.

Before reading further, it’s worth taking some time to think about why the leaf in the photo is beautiful; and making sure you’re clear on how harmony, symmetry, order and unity add to the beauty of the whole.

Some historical background

In his writings Edwards is consciously engaging with the great thinkers who came before him. From the Greek philosophers until the Enlightenment there was a certain degree of consensus about beauty – that proportion, unity and symmetry are essential to it:

According to the great theory of beauty, it is … the harmony of the parts to a whole that constitute what is beautiful. For the ancients, order and harmony of parts were chief components of beauty—unity, balance, and symmetry.

Matthew Capps, Reimagining beauty

How Edwards develops this – Beauty as relationship

But Edwards wants to go further. He writes:

Some have said that all excellency (beauty) is harmony, symmetry or proportion; but they have not yet explained it.

Edwards, The Mind

Louis Mitchell writes that Edwards ‘accepts (the) traditional definition of beauty as regularity or proportionality; but he is not satisfied with that definition. He wants to know why beauty is what it is… (His answer) is that beauty in its elementary form consists in a certain relatedness between entities. This relatedness involves a similarity or likeness of one kind or another.’ (Louis Mitchell, Jonathan Edwards on the Experience of Beauty).

In other words, beauty is relational in nature. At the very heart of beauty is relationship. This relationship can take various forms, and we will briefly consider a few.

It is worth noting that the study of beauty is an art not a science, and therefore as we seek to categorise aspects of beauty there is a danger that we lose something of the beauty of the whole – rather like when we study the properties of an insect we deprive it of life in the process. I hope the reader will forgive this, as well as the fact that Edwards and his students can be quite dense to follow sometimes, and therefore I have no doubt that my own understanding will progress in due course (and I may need to make changes to this post as a result!)

Types of beauty

Simple beauty

Edwards writes: ‘Proportion is a thing that may be explained yet further. It is an equality, or likeness of ratios; so that it is the equality that makes the proportion. Excellency (beauty) therefore seems to consist in equality.’ (The Mind).

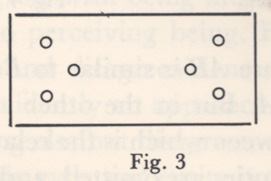

What does he mean by equality? He writes later that ‘all beauty consists in identity of relation’. So where there is an identical relation between entities, there is beauty. He goes on to illustrate with a variety of diagrams, the most complicated of which is shown below.

Edwards notes that there are a great number of equalities (that is, equalities of relation) in this diagram. For example, the three circles on each side form an equilateral triangle; the four sides form a rectangle; the two triangles are in equal relation within the rectangle and so on. Furthermore, the more equalities there are, the more beautiful it is. The diagram is more beautiful with the two equilateral triangles than it would be if there were only one.

Thus we see the role of harmony, equality, symmetry and unity in ‘simple beauty.’ And at the heart of it is an equal relatedness of each part to the whole.

Design / relatedness to the whole

Mention of ‘the whole’ brings up another important aspect of beauty – the beauty of something is relative to how it fits into a bigger whole. Edwards writes:

Thus the uniformity of two or more pillars, as they may happen to be found in different places, is not an equal degree of beauty as that uniformity in so many pillars in the corresponding parts of the same building. So means and an intended effect are related one to another.

Nature of True Virtue

Thus a thing is more beautiful if it is part of a greater design – if it serves a purpose. In the Nature of True Virtue, Edwards takes this to the extreme and talks about relatedness to ‘being in general’ by which he means God. The more closely related a thing is to God, the more beautiful it is.

Kin Yip Louie writes:

In Edwards, uniformity cannot be measured by mere equality of the parts. The parts joined together in harmonious proportion for a singular purpose gives it an extra dimension of beauty.

Yin Kip Louie, The Theological Aesthetics of Jonathan Edwards

Complex beauty

Edwards writes ‘Proportion is complex beauty.’ (The Mind). He illustrates what he means by referring to various sequences of lines. Kin Yip Louie explains the same concept in terms of sequences of numbers:

In a complex design, we may have to give up simple beauty for the sake of complex beauty. Consider the two sets

A = {1, 3, 4, 9}

B = {2, 6, 8, 18} Judging A or B by itself, the numbers in them are chaotic and without beauty. Putting A and B together, we see the proportion between the two sets and chaos turns into beauty.*

Yin Kip Louie, The Theological Aesthetics of Jonathan Edwards

Notice that there is still a relationship – an ‘identity of relation’ between the numbers, but in this case it is more complex. And to the extent it is more complex, Edwards argues, it is more beautiful.

Intensified beauty

Edwards also sees beauty in disproportions being brought together into a greater unity. He writes that ‘particular disproportions sometimes greatly add to the general beauty, and must necessarily be in order to a more universal proportion.’ (The Mind).

Mitchell explains:

Beauty can be intensified through the harmonization of disproportions, inequalities or irregularities. The intensification of beauty is accomplished through a conjunction of diverse, even antithetical, qualities. The more inequalities and irregularities that can be conjoined into a proportional relation, the greater and more intensified the beauty.

Louis Mitchell, Jonathan Edwards on the Experience of Beauty

We will find intensified beauty particularly relevant when we consider the beauty of Christ and of God’s providence in future posts.

Illustration through music

Mitchell explains that many of these concepts regarding beauty are best understood using the example of music:

Voices singing in unison portray a simple beauty of equality, each individual voice singing the same notes (simple beauty). However, a choir singing in four-part harmony evidences a more sophisticated beauty. Although the various voices are not singing the same notes, the notes are proportionately related through harmony (complex beauty). The more sophisticated the relations, the more intensified the beauty becomes. Thus the music produced by a large choir, accompanied by a full orchestra… may be said to be intensely beautiful.

Louis Mitchell, Jonathan Edwards on the Experience of Beauty

Secondary beauty

As we saw in the previous post, Edwards is also original in distinguishing between primary and secondary beauty. The things that we usually consider beautiful – a work of art, a view, a piece of music – are examples of secondary beauty. ‘Secondary beauty’ is thus the beauty of equality / harmony / symmetry / proportion in the material world. In the following quote we can see how Edwards observes the different ‘aspects’ of beauty we’ve already considered, in the natural world:

And so in every case, what is called correspondency, symmetry, regularity and the like, may be resolved into equalities; though the equalities in a beauty in any degree complicated are so numerous that it would be a most tedious piece of work to enumerate them. There are millions of these equalities. Of these consist the beautiful shape of flowers, the beauty of the body of man and of the bodies of other animals. That sort of beauty which is called “natural,” as of vines, plants, trees, etc., consists of a very complicated harmony; and all the natural motions and tendencies and figures of bodies in the universe are done according to proportion, and therein is their beauty. Particular disproportions sometimes greatly add to the general beauty, and must necessarily be, in order to a more universal proportion—so much equality, so much beauty—though it may be noted that the quantity of equality is not to be measured only by the number, but the intenseness, according to the quantity of being. As bodies are shadows of being, so their proportions are shadows of proportion.

The Mind

Primary beauty

As we saw in the first post and will see in future posts, for Edwards the relationships which form the beauty of creation are a visible picture graciously given to us by God for a deeper beauty: the relationships between spiritual beings. Edwards writes:

This is a universal definition of excellency (beauty): the consent of being to being… The more the consent is, and the more extensive, the greater the excellency.

The Mind

Edwards tells us how primary and secondary beauty relate to each other in ‘The Nature of True Virtue’:

That consent, agreement, or union of being to being, which has been spoken of, viz. the union or propensity of minds to mental or spiritual existence, may be called the highest, and first, or primary beauty that is to be found among things that exist: being the proper and peculiar beauty of spiritual and moral beings, which are the highest and first part of the universal system for whose sake all the rest has existence. Yet there is another, inferior, secondary beauty, which is some image of this, and which is not peculiar to spiritual beings, but is found even in inanimate things: which consists in a mutual consent and agreement of different things in form, manner, quantity, and visible end or design; called by the various names of regularity, order, uniformity, symmetry, proportion, harmony, etc. Such is the mutual agreement of the various sides of a square, or equilateral triangle, or of a regular polygon. Such is, as it were, the mutual consent of the different parts of the periphery of a circle, or surface of a sphere, and of the corresponding parts of an ellipse. Such is the agreement of the colors, figures, dimensions, and distances of the different spots on a chess board. Such is the beauty of the figures on a piece of chintz, or brocade. Such is the beautiful proportion of the various parts of an human body, or countenance. And such is the sweet mutual consent and agreement of the various notes of a melodious tune.

Nature of True Virtue

So what?

Many of the concepts considered in this post are complex and may appear quite abstract. Why are they important? And why is this relevant for us today?

The concepts are relevant because they begin to give us contours as to what it is that we appreciate about beauty. As we saw in the first post, beauty is not a merely subjective concept – it has objective substance. It can be ‘studied’ (though not in an entirely scientific way). And I have found that as I understand more about why I appreciate the beauty of something, it increases the appreciation of the beauty and the resulting praise – something that will no doubt continue to happen for all eternity (Ephesians 2:7).

As regards their importance: Having defined what we mean by beauty, we’re now in a position to consider the different ‘beauties’ that God has provided for our blessing, and how we can discover the beauty of God through them. By way of reminder, Strachan tells us there is a

Cycle of beauty that begins with the Lord, extends to creation, takes personal bodily form in Christ, is displayed corporately by the Church, (and) culminates in heaven.

Strachan and Sweeney, Jonathan Edwards on Beauty

God is the source of beauty – the foundation of beauty. And part of his beauty is to overflow. And thus he created. And he has created various means by which we see beauty and appreciate his beauty more and more. Over the next few posts we’ll think about the different things in that list, and how they lead us to the beauty of God which we were made to enjoy and be part of.

Finally, the concepts are important because they remind us again of the fundamental significance of relationship: that relatedness among entities is at the very heart of beauty. This applies both to physical beauty; but also to spiritual beauty – indeed, (as we have seen and will see again) the greatest beauty of all is the relationship of love between spiritual beings, and supremely the love of the Trinity.

Taking it further

Jonathan Edwards on the Experience of Beauty – Louis Mitchell

Reimagining Beauty – An Enquiry into the Role of Beauty and Aesthetics in the Spiritual formation of Congregations – Matthew Capps

The Theological Aesthetics of Jonathan Edwards – Yin Kip Louie

The key works by Jonathan Edwards in this area are The Mind; and Nature of True Virtue.

*The sequence of numbers is the same in the two sets – so taken together, there is a beauty which is not present when one sequence is taken on its own.